The play Constellations begins with two people, Roland and Marianne, meeting for the first time. It’s a short scene, and it doesn’t go well. Then the lights go down, come back up, and it’s as if the scene has reset itself. The characters meet for the first time, again, but with slightly different (still unfortunate) results.

The entire play progresses this way, showing multiple versions of different scenes between Roland, a beekeeper, and Marianne, an astrophysicist.

In the script, each scene is divided from the next by an indented line. As the stage notes explain: “An indented rule indicates a change in universe.”

To scientist Richard Partridge, who recently served as a consultant for a production of Constellations at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley, it’s a play about quantum mechanics.

“Quantum mechanics is about everything happening at once,” he says.

We don’t experience our lives this way, but atoms and particles do.

In 1927, physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg wrote that, on the scale of atoms and smaller, the properties of physical systems remain undefined until they are measured. Light, for example, can behave as a particle or a wave. But until someone observes it to be one or the other, it exists in a state of quantum superposition: It is both a particle and a wave at the same time. When a scientist takes a measurement, the two possibilities collapse into a single truth.

Physicist Erwin Schrodinger illustrated this with a cat. He created a thought experiment in which the decay of an atom—an event ruled by quantum mechanics—would trigger toxic gas to be released in a steel chamber with a cat inside. By the rules of quantum mechanics, until someone opened the chamber, the cat existed in a state of superposition: simultaneously alive and dead.

Some interpretations of quantum mechanics dispute the idea that observing a system can determine its true state. In the many-worlds interpretation, every possibility exists in a giant collection of parallel realities. In some, the cat lives. In others, it does not.

In some Constellations universes, the astrophysicist and the beekeeper fall in love. In others, they do not. “So it’s not really about physics,” Partridge says.

Constellations director Robert Kelley, who founded TheatreWorks in 1970, agrees. He says he was intimidated by the physics concepts in the play at first but that he was eventually drawn to the relationship at its core.

“With all of these things swirling around in the play, what really counts is the relationship between two people and the love that grows between them,” he says. “I found that a very charming message for Silicon Valley. We’re surrounded by a whole lot of technology, but probably for most people what counts is when you get home and you’re on the couch and your one-and-a-half-year-old shows up.”

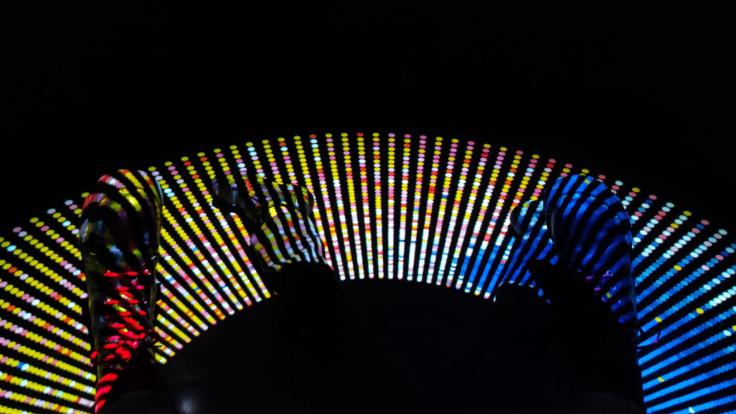

TheatreWorks in Silicon Valley production of Constellations

Kelley says that he found something familiar in the many timelines of the play. “It’s really kind of fun to see all that happen because it’s common ground for us as human beings: You hang up the phone and think, ‘If only I’d said that or hadn’t said that.’ It’s a fascinating thought that every single thing that happens will then determine every single other thing that happens.”

Constantly resetting and replaying the same scenes “was very acrobatic,” says Los Angeles-based actress Carie Kawa, who played Marianne in the TheatreWorks production, which concluded in September. “And there were emotional acrobatics—just jumping into different emotional states. Usually you get a little longer arc; this play is just all middles, almost like shooting a film.”

To her, the repeats and jumps were familiar in a different way: They were an encapsulation of the experience of acting.

“We do the play over and over again,” she says. “It’s the same scene, but it’s different every single time. And if we’re doing it right, we’re not thinking about the scene that just happened or the scene that’s to come, we’re in the moment.”

The play will mean different things to different people, Kawa says.

“A teacher once told me a story about theater and a perspective that he had,” she says. “At first he said, ‘Theater is important because everybody can come together and feel the same feeling at the same time and know that we’re all okay.’

“But as he progressed in this artistry he realized that, no, what’s happening is everybody is feeling a slightly different feeling at the same time. And that’s OK. That’s what helps us experience our humanity and the humanity of the other people around us. We’re all alone in this together.”